James Copnall

BBC Newsday presenter

AFP

AFP

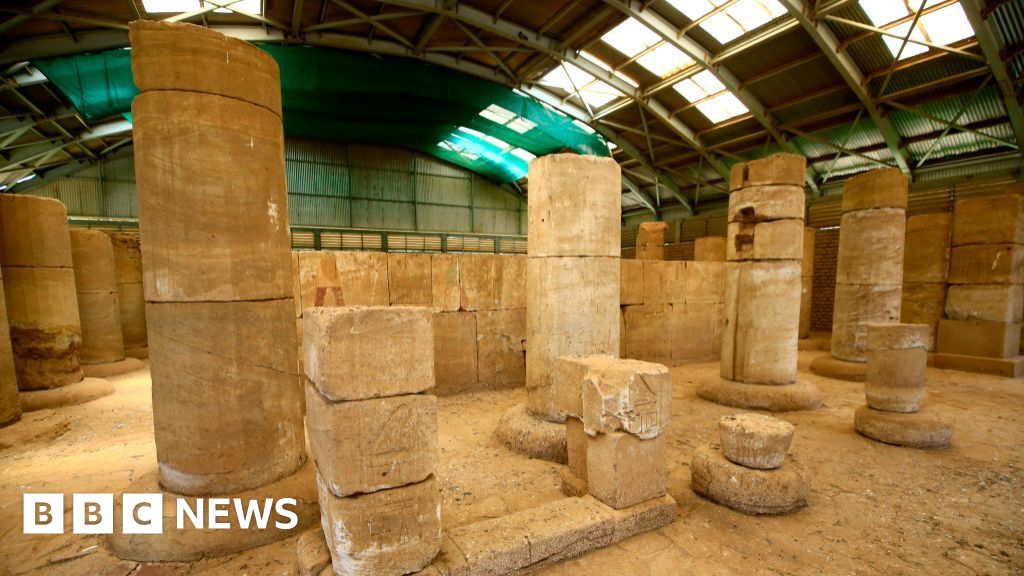

The Sudan National Museum (pictured here before it was looted) is home to important pieces from ancient Nubian civilisations

Imposing statues of rams and lions used to stand in the grounds of Sudan’s National Museum – priceless artefacts from the time when Nubian rulers conquered what is now Egypt to the north, along with exquisite Christian wall paintings dating from many centuries ago.

On a typical day, groups of school children would stare in awe at this reminder of their nation’s imposing past, tourists would file through one of Khartoum’s must-sees, and on occasion concerts were held in the grounds.

But that was before war broke out two years ago.

As the Sudanese military reasserts its control over the capital, having finally chased out its rival the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the full scale of the destruction of two years of war is becoming clear.

Government ministries, banks and office blocks stand blackened and burned, while the museum – a symbol of the nation’s proud history and culture – has been particularly hard hit.

Senior officials say tens of thousands of artefacts were either destroyed or shipped off to be sold during the time the RSF was in control of central Khartoum, where the museum is situated.

“They destroyed our identity, and our history,” Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed, director of museums at Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, told the BBC’s Newsday programme.

Before the conflict, the National Museum was a gem.

Located at the very heart of Sudan – close to the Presidential Palace, and the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile rivers – it told a story of the succession of great civilisations that inhabited this area over time.

Now, when museum officials made an inspection visit, they were greeted with shattered glass, bullet cases on the floor and traces of looting everywhere.

“The building was very unique and very beautiful,” Ms Ahmed said.

“The militia [the description Sudanese officials give to the RSF] took so many of the unique and beautiful collections, and destroyed and damaged the rest.”

Julie Anderson

Julie Anderson

The museum’s entrance before the war began…

Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed

Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed

… and after

Looting has been reported at other Sudanese museums and ancient sites. Last September the UN’s world heritage organisation, Unesco, warned of a “threat to culture” and urged art dealers not to import or export artefacts smuggled out of Sudan.

Before the war, the National Museum was undergoing rehabilitation, and so many of its treasures were boxed up.

That may have made it easier for the collections to be removed.

Sudanese officials say precious artefacts from the National Museum were taken away to be sold.

They strongly suspect RSF fighters took some of the valuables to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UAE has been widely accused of funding the RSF, although both parties have always denied these accusations.

“We had a strong room for the gold collection, they managed to open it and took all the gold,” Ms Ahmed said.

“Maybe they kept it for themselves, or maybe they traded it in the market.”

So the whereabouts of pieces like a gold collar from the pyramid of King Talakhamani at Nuri, which dates to the 5th Century BC, are unknown.

Asked about the value of what was taken, Ms Ahmed replied simply: “There is no value for the museum artefacts, it’s more expensive than you could imagine.”

Rocco Ricci © The Sudan National Museum

Rocco Ricci © The Sudan National Museum

A collar from the pyramid of King Talakhamani is among the missing gold pieces

AFP

AFP

Many of the artefacts that remain have been damaged

The de facto government of Sudan says it will contact Interpol and Unesco to attempt to recover artefacts looted from the National Museum and elsewhere.

However recovering the artefacts seems a difficult and perhaps even dangerous task, with little immediate prospect of success.

The government, and other Sudanese observers, say the RSF’s attacks against museums, universities and buildings like the National Records Office are a conscious attempt to destroy the Sudanese state – but, again, the RSF denies this.

Amgad Farid, who runs the Fikra for Studies and Development think-tank, is particularly critical of the looting.

“The RSF’s actions transcend mere criminality,” he wrote in a piece shared by his organisation.

“They constitute a deliberate and malicious assault on Sudan’s historical identity, targeting the invaluable heritage of Nubian, Coptic, and Islamic civilisations spanning over 7,000 years, constituting a cornerstone of African and global history, enshrined within these museums.

“This is not an incidental loss amid conflict – it is a calculated endeavour to erase Sudan’s legacy, to sever its people from their past, and to plunder millennia of human history for profit.”

Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed

Ikhlas Abdel Latif Ahmed

The extent of the looting became apparent after the RSF was forced out of Khartoum

The story of the National Museum – taken over by armed men, its gold and valuables looted and stolen – mirrors the individual stories of so many Sudanese in this conflict: they have been forced to flee, their houses occupied, their gold stolen.

According to the UN, nearly 13 million people have been forced from their homes since the fighting began in 2023, while an estimated 150,000 people have been killed.

“The war is against the people of Sudan,” Ms Ahmed says, bemoaning the war’s human cost, as well as the unimaginable loss of centuries of heritage.

She – along with other like-minded individuals – intend to restore the National Museum and other looted institutions.

“Inshallah [God willing] we will get all our collections back,” she said.

“And we build it more beautiful than before.”

More about the war in Sudan from the BBC:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC