Andrew Rogers

BBC Newsbeat

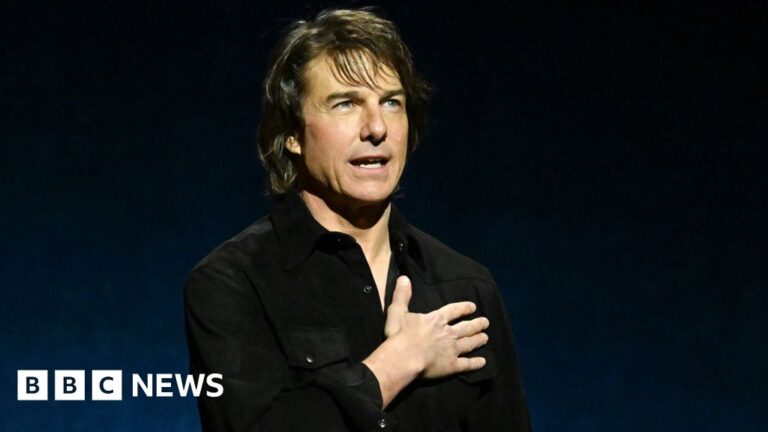

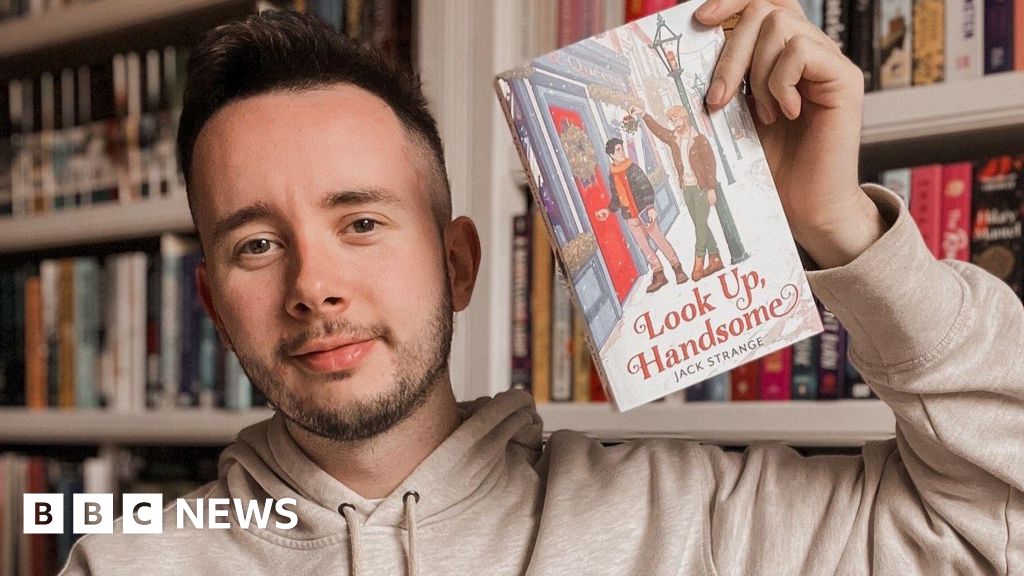

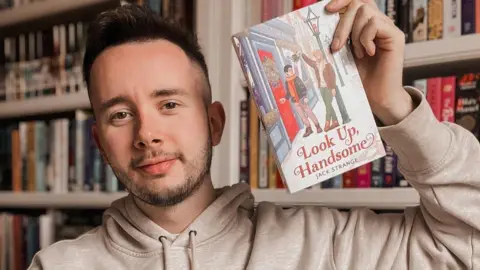

Jack Strange

Jack Strange

Jack landed his dream publishing deal last year but found his self-published works had been scraped

Landing a publishing deal was a dream come true for Jack Strange.

“It was incredible. I’d had so many rejections along the way,” he says.

“So when someone said yes, I cried because it’s everything I ever wanted.”

Before Jack published debut novel Look Up, Handsome, he’d written other, self-published titles.

But he felt an entirely different emotion when he found out that those works had appeared on LibGen – a so-called “shadow library” containing millions of books and academic papers taken without permission.

An investigation by The Atlantic magazine revealed Meta may have accessed millions of pirated books and research papers through LibGen – Library Genesis – to train its generative AI (Gen-AI) system, Llama.

Now author groups across the UK and around the world are organising campaigns to encourage governments to intervene.

Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, is currently defending a court case brought by multiple authors over the use of their work.

‘More difficult with AI coming in’

Llama is a large language model, or LLM, similar to Open AI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini.

The systems are fed huge amounts of data and trained to spot patterns within it. They use this data to create passages of text by predicting the next word in a sequence.

Despite the systems being labelled intelligent, critics argue LLMs do not “think”, have no understanding of what they produce and can confidently present errors as fact.

Tech companies argue that they need more data to make the systems more reliable, but authors, artists and other creatives say they should pay for the privilege.

A Meta spokesperson told BBC Newsbeat it had “developed transformational GenAI powering incredible innovation, productivity and creativity for individuals and companies”.

They added that “fair use of copyrighted materials is vital to this”, and that the company wants to develop AI that benefits everyone.

As well as concerns over copyright and accuracy, AI systems are also power-hungry, prompting environmental fears, and worries they could threaten jobs.

Facing down a trillion dollar company

While Jack’s debut novel wasn’t part of the LibGen dataset, he did find some of his self-published books had been taken.

He says he wasn’t surprised because he’d seen so many fellow authors affected, but that it did spur him on to want to do something about it.

“There’s always something you can do. You can’t just say ‘oh well’. You’ve got to speak up and fight back,” he tells BBC Newsbeat.

Meta says open source AI like Llama will “increase human productivity, creativity, and quality of life”.

But Jack says it poses a real risk to creatives like him.

“It’s annoying that the first thing AI comes for are creative jobs that bring you joy.

“We’re so undervalued already, and we’re even more undervalued now with AI coming in.”

Jack says going up against a company like Meta, which is worth more than a trillion dollars, doesn’t feel like a fight he can take on alone.

“How much control can you take back when your work has already been taken?

“How do we live with that and how do we get protected from that?”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Meta says it wants to develop AI for everyone’s benefit

He’s one of a growing number of writers calling on the government to intervene, with a demonstration planned on Thursday near Meta’s London office, as well as action online.

Abie Longstaff works at the Society of Authors, a union representing writers, illustrators and translators, and tells Newsbeat they have been raising concerns about the risks of AI for years.

“We all feel that level of helplessness,” she says. “But we’re all fighting so hard.”

She says her work has also been stolen and used to train AI, something she believes has an impact on future publishing opportunities.

“Large language models work by prediction, they work by looking at patterns. They want our voice, they want our expression, they want our style.

“So you can as a normal person go onto one of these sites and say ‘please can you write me a book in the style of Abie Longstaff’ and they’ll write it in my style, in my voice.”

Because their works have been scraped though, writers won’t get any compensation or recognition if it’s used this way.

“We want to see compensation, we want to see that it’s more transparent,” Abie says.

“The company has taken our books and used it to make money. It has money, but instead of paying us for our intellectual property instead of licensing a word, it’s taking it all for free.”

The Society of Authors as well as other unions like the Writers’ Guild are encouraging writers to get in touch with their MPs to raise their concerns in government.

In December, the government shared a consultation in a bid to navigate the issue between copyright holders being in control and paid for their work and AI companies having “wide and lawful access to high-quality data”.

One proposal was giving tech companies automatic access to works such as books, films and TV shows to train AI models unless creators opted out.

But Abie thinks that’s the wrong way round.

“It’s like saying you’ve got to put a note on your wallet saying no-one steal it,” she says.

“It should be the AI companies asking us if they can use our work.”

Writing is something Jack had always dreamed of doing – and still does, despite the challenges he’s currently facing.

“It’s still my dream to be an author and hopefully write full time. It’s incredibly difficult now, it’s going to be more difficult with AI coming in.”

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays – or listen back here.